From Flooding to Drought and Back Again: Handling Weather Extremes With Stormwater Management

Sometimes, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing. When rain is sparse, drought becomes a concern and people wonder if aquifers, wells, or reservoirs are running low. When torrential flooding rains hit, we struggle to cope with too much water.

Flooding events can be devastating, and data trends suggest that we have been getting more heavy rainfalls between the dry periods. To prepare for these events, there are planning responses to consider: simply rebuild and hope it doesn’t happen again, rebuild with armoring and/or raised elevations, or retreat or relocate if an area is so prone to flooding that continual rebuilding is neither practical nor financially sensible (an option rarely considered).

There is one more approach to consider: find ways to reduce the peak flood levels. After all, it is the peak flood energies—those final few inches or feet of flood cresting that are too high and cause currents that are too extreme—which usually cause the most damage. Hydrogeologists suggest that thoughtful groundwater management can limit damaging flood peaks. To be successful, these tactics need to be implemented broadly across the full collection area of our streams and rivers.

Jim Tierney, the Deputy Commissioner of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Office of Water Resources, once said at a Hudson River Watershed Alliance conference that the best way to manage floodwaters is to slow it down, spread it out, and soak it in. By doing this, floodwater reaches a stream more gradually, more of it gets absorbed along the way, and peak flows for each individual stream do not simultaneously converge at downstream locations.

Hydrogeologists also appreciate Tierney’s advice because slowing water down allows more to sink into the ground, which contributes to groundwater recharge to keep our aquifers replenished and wells supplied.

Thoughtful Groundwater Management

So, how do we slow it down, spread it out, and soak it in? In 2008, a volunteer professional working group gathered in Dutchess County, New York, to create “Recommendations for Stream & Flood Management in Dutchess County.” These recommendations were developed to address flooding threats in Dutchess County but are relevant everywhere. There are many actions, big and small, which can help.

Here are just a few of the recommendations and ideas:

Enforce Stormwater Regulations

Many states require stormwater management planning as part of permitting for new development projects. Broadly speaking, these regulations seek to detain peak floodwater volumes, soak some of it in, and then release the detained water slowly in ways that minimize high peak flows. Project applicants and planning board reviewers should strive to satisfy these regulations, and when there are choices, choose the options that slow down and soak in the rainfall.

Upsize Bridges and Priority Culverts

Municipalities can consider increasing bridge spans and culvert sizes where debris blockages repeatedly occur during flood events. Ensure that such widening leaves room for streams to naturally migrate in their beds as well. Some of these corrective actions can also ensure fish connectivity in streams, but be aware, however, that many existing culverts currently cause beneficial stormwater detention where they briefly slow and spread stormwater in harmless ways along roadsides. These detained flows are temporary following a storm event and help limit downstream flooding. While not the original intent, these culverts represent a wide array of existing detention structures. Upsizing every culvert without thought risks inadvertently increasing downstream peak flooding.

Mow Versus Scour

Roadside drainage should be configured to allow for regular mowing rather than bare earth ditches. Vegetated berms help slow groundwater flow and can capture sediments. Roadside drainage should ideally distribute road runoff through detention ponds or constructed wetlands so water can further slow before entering streams. Be careful, however, about intentionally recharging road runoff since this can lead to rising salt in groundwater. It is often better to keep salt in the surface water environment, rather than groundwater, since surface water moves through and away from an area more quickly than slow groundwater migration pathways.

Avoid Unnecessary Clearing

Channel clearing and removal of woody debris and gravel from streams should be avoided. Attempting to direct natural stream activity can be futile and disruptive to fisheries and natural vegetation communities. Wood removal at sites posing an imminent threat to critical infrastructure should still be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Leave Floodplains Be

Floodplain areas should be kept undeveloped and naturally vegetated, ensuring that floodwater overflow areas remain accessible when water needs extra space. Both floodplains and complex channels help slow floodwater movement, reducing flood crest elevations at downstream locations.

Attain FEMA Eligibility

Communities are encouraged to participate in local and regional planning, ensuring eligibility for FEMA support, including leveraged buyout funding for repeatedly flooded properties. Buyout programs are sometimes the wisest planning strategy where growth has placed development in flooding’s way. Restoring prior flood zone areas also helps reduce downstream flood crest levels.

Expand Temporary Water Storage

Explore opportunities to expand temporary stormwater detention on restored or existing wetlands and existing or expanded floodplains.

Recharging Our Groundwater

Short, heavy rainfalls typically do not recharge groundwater much because there is little time for absorption. Long, slow rainfalls allow time for absorption and therefore provide more beneficial aquifer recharge. Slowing stormwater down can resemble a long, slow rainfall. The recommendations reviewed above for slowing stormwater are almost all also beneficial to groundwater recharge and aquifer resilience.

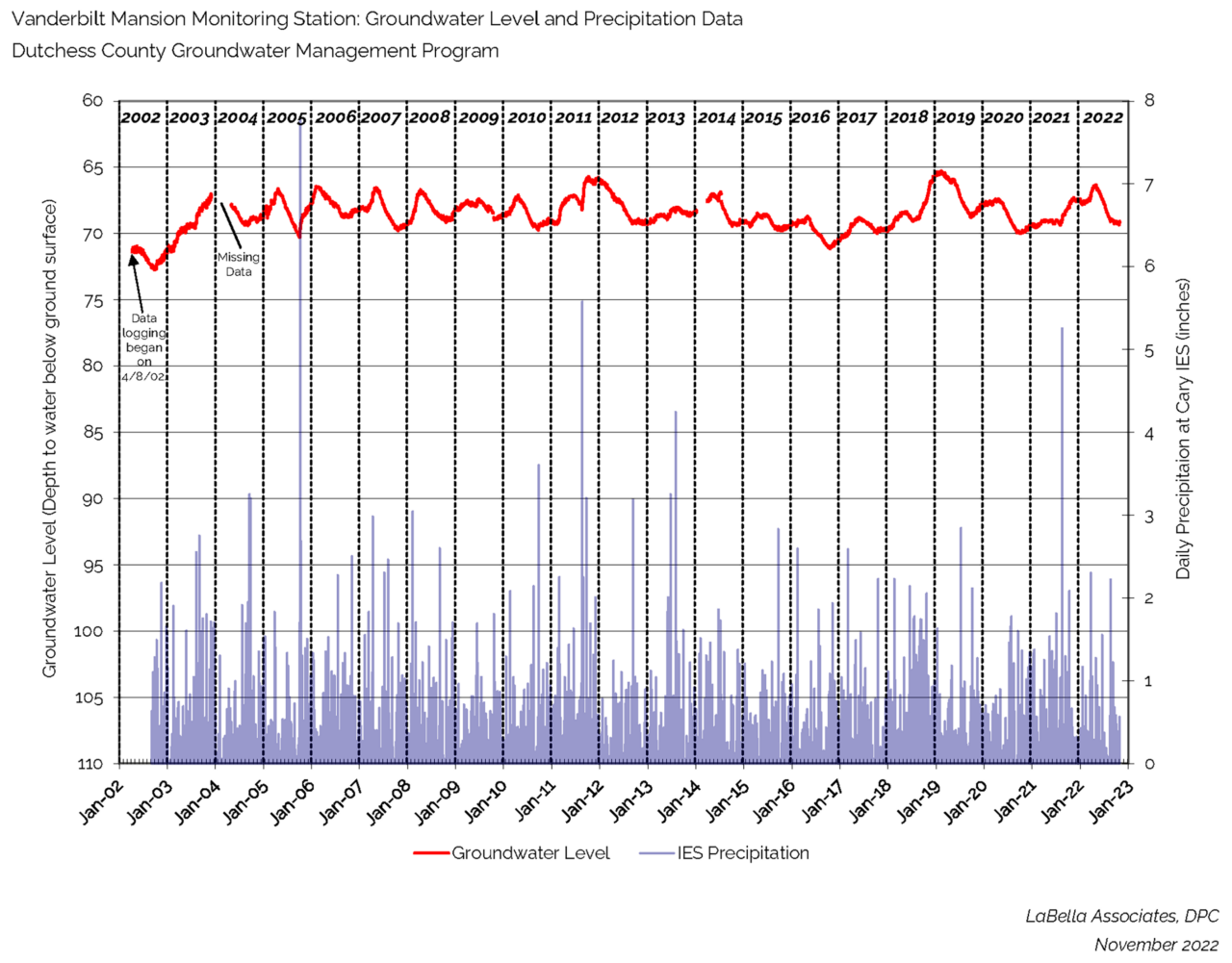

LaBella Associates has helped Dutchess County, in eastern New York State, develop and maintain an aquifer water level monitoring program since 2001. The data shows that year-over-year Dutchess County aquifers remain full of groundwater, replenished by annual precipitation of approximately 40 inches.

*Annual groundwater level and precipitation data (2002-2022) obtained from the Vanderbilt Mansion monitoring station, as part of the Dutchess County Groundwater Management Program.

Aquifers are recharged principally during the non-growing season (autumn to spring) when vegetation and evaporation do not intercept and consume most precipitation. During summer, groundwater levels decline naturally as water seeps out slowly into wetlands and streams, is used by plants, or is withdrawn by wells. This cycle repeats itself every year, with small variations annually as we receive more or less rainfall.

So, as we think about storms and experience increasingly heavy rain events and flood damage, there are a wide range of protective and planning strategies that can be adopted or advocated for by municipalities. These practices can collectively help cope with significant stormwater flooding challenges while also supporting groundwater recharge. Remember: slow it down, spread it out, soak it in!

About the Author

Russell Urban-Mead, PG, CPG, QEP, LEED APVice President, Senior Hydrogeologist

As a Senior Hydrogeologist and Environmental Scientist with over 30 years of experience, Russell leads groundwater supply and resource management evaluations, co-leads stormwater design and climate adaptation design project teams, and contributes to or leads environmental remediation programs for contaminated groundwater sites, including inactive hazardous waste sites, brownfields sites, gasoline stations and related sites. He specializes in water resource and water supply development and planning, establishing aquifer monitoring and wellhead protection programs for communities, supporting shoreline and stream corridor restoration programs, and developing high-yield wellfields for municipal and privately regulated community water system clients.