Rooted in Community: Rural Design Considerations for K-12 Schools

Rural schools face unique challenges—from limited resources and geographic isolation to staffing constraints and shifting community needs. But they also offer opportunities for innovation, creativity, and community-rooted learning experiences.

In this interview, we sought insight from three members of our LaBella team who have extensive experience and valuable perspectives on designing and managing K-12 projects: Justin Shaffer, an architect and project manager with more than a decade of experience in the K-12 market; Courtney Ter Velde, a NYS Certified Interior Designer and Accredited Learning Environment Planner; and Glenn Niles, a former superintendent and school administrator with over 25 years of experience in education.

Below, we explore how we plan and design tailored, creative learning experiences in rural communities—and how we can better support educators and students through project design.

How does your design approach differ when working on a school project in a rural area versus an urban or suburban area?

Courtney Ter Velde: The approach for designing any K-12 project includes the process of design, pre-referendum, and submission phases. We would want to hit the same hallmarks whether it is an urban, suburban, or rural school. Regardless of the size of the school or district, we ensure that the approach is the same. One way that can be unique when approaching the design at a rural school versus an urban or suburban school is the community. Understanding the heart of the community—its values and priorities—helps to determine the desires not only of school administrators and staff but also of students, parents, and the broader community’s expectations for a graduate profile. Meeting with the community to gain an understanding of its unique aspects and history is paramount. We aim to inject highly valued history and culture into modern design approaches without losing that sense of identity.

Courtney Ter Velde: The approach for designing any K-12 project includes the process of design, pre-referendum, and submission phases. We would want to hit the same hallmarks whether it is an urban, suburban, or rural school. Regardless of the size of the school or district, we ensure that the approach is the same. One way that can be unique when approaching the design at a rural school versus an urban or suburban school is the community. Understanding the heart of the community—its values and priorities—helps to determine the desires not only of school administrators and staff but also of students, parents, and the broader community’s expectations for a graduate profile. Meeting with the community to gain an understanding of its unique aspects and history is paramount. We aim to inject highly valued history and culture into modern design approaches without losing that sense of identity.

Glenn Niles: Those are great points. The close-knit culture at rural schools is distinctive. It’s less common to see in an urban school district, outside of smaller elementary schools. The school is often the center of the community, which can make a big difference in terms of the design. It’s important we maintain the school and community history while modernizing the buildings.

Glenn Niles: Those are great points. The close-knit culture at rural schools is distinctive. It’s less common to see in an urban school district, outside of smaller elementary schools. The school is often the center of the community, which can make a big difference in terms of the design. It’s important we maintain the school and community history while modernizing the buildings.

Justin Shaffer: Most rural school districts have fewer buildings than their suburban and urban counterparts, with most having a single building housing grades K-12. Because of this, money tends to go further, since it can be applied to more square footage within one building, as opposed to being divided across multiple facilities. For example, if a district has an approved project budget of $20 million but 10 separate buildings, those resources will be spread thin. With just one building, however, we can focus more strategically on their needs and potentially update or renovate half the building within a single project.

Justin Shaffer: Most rural school districts have fewer buildings than their suburban and urban counterparts, with most having a single building housing grades K-12. Because of this, money tends to go further, since it can be applied to more square footage within one building, as opposed to being divided across multiple facilities. For example, if a district has an approved project budget of $20 million but 10 separate buildings, those resources will be spread thin. With just one building, however, we can focus more strategically on their needs and potentially update or renovate half the building within a single project.

Courtney Ter Velde: To add to that, projects in a single building tend to have a greater impact on the students and staff. Updating the one shared library for grades 6–12 benefits all students directly, supporting curriculum growth, tech integration, and project-based learning. In larger districts with multiple schools, renovating one library benefits a smaller portion of the student population.

You mentioned culture and community are paramount when designing for rural districts. Can you elaborate on how the planning process is centered around the community?

Courtney Ter Velde: From the start, we ensure that we are helping to facilitate the community’s needs and goals through a series of focus groups and visualization sessions. These can include touring other schools with administrators, gathering feedback from different community groups and business owners, and talking with students directly. Using that context and knowledge base informs the planning and design in a transparent way. From there, we’re more prepared to execute a successful project if everybody responds positively, feeling that their input has been heard.

Glenn Niles: Stakeholder groups in rural areas are a bit broader. Engaging a large group throughout the entire process—particularly during pre-referendum and before proposed projects go to vote—can be beneficial in rural districts. By clearly conveying the proposed improvements to the community and explaining the tax and cultural impacts, buy-in becomes more likely.

Justin Shaffer: In rural districts, staff and administrators often live within the district’s boundary. These synergies can be very helpful. Their direct experience regarding what impacts not only the school but also the broader community can help inform the design earlier in the process.

Is space utilized differently compared to urban and suburban schools?

Justin Shaffer: For curriculum programming, districts are working with the staff, students, and design team to develop and build spaces where more technical or vocational learning can take place. Due to shifting enrollment numbers in rural districts, there’s often flexibility within the existing school footprint to create hands-on learning environments without the need for an addition—making the upgrades more cost-effective. We’ve merged classrooms into larger spaces to accommodate the creation of STEAM areas, hydroponics labs, and career and technical education spaces that allow students to graduate with certifications or college credits. The key differences in design often relate to the types of programs and trade skills being offered. For example, a program with an agricultural component requires a different setup than one focused on automotive technology or robotics.

Glenn Niles: Another reason this is so beneficial is the distance between districts in rural areas can be significant. By using underutilized space, more programming can be done directly in schools now rather than busing students to offsite programs.

Courtney Ter Velde: And it’s not always multiple classrooms or large underutilized spaces that are necessary to design areas where alternative programming can take place. One of the districts we work with has a relatively small middle/high school library, and the librarian has created offshoot programs based on student interests—like sewing and esports gaming. In a smaller community, there is often a greater opportunity to keep a finger on the pulse of what’s most important to students.

Are there any specific technological needs for students in rural districts that might not be as critical in urban or suburban areas?

Courtney Ter Velde: Yes, Wi-Fi in particular. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many students in rural areas had to sit in their school parking lots to attend classes and complete coursework, as it was often the only place they could access Wi-Fi. In many rural areas, continuous internet access is not readily available. The school may be one of the only places where students and the community at large can access Wi-Fi, opening up opportunities for activities such as job searching and applications, research, and homework.

Glenn Niles: Some districts will open the library for extended hours, not only after school but also in the evening, so that community members can get Wi-Fi access or use computers.

Are there other types of design considerations that take the public’s needs into account?

Courtney Ter Velde: Absolutely—any type of space where you’d have the potential for community use. Resource centers, for example, can support not only students but parents and families as well. Parents can access information about available services, and students can fill out college applications, among other uses.

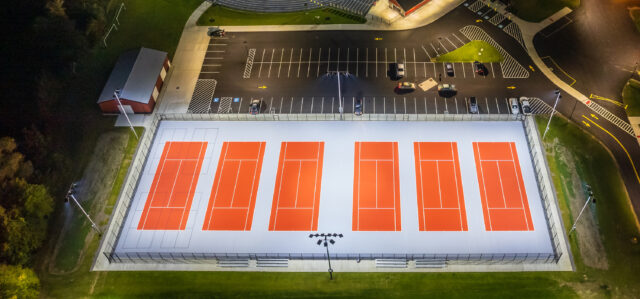

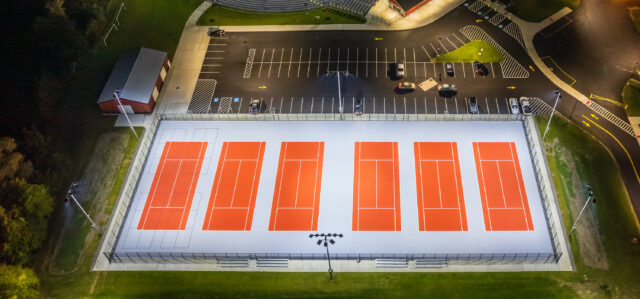

Wellness resources are also important. Many rural districts offer free or low-cost access to their facilities, including the track, tennis courts, swimming pool, gymnasium, and fitness and weight rooms. As an example of a community-focused design consideration, we recently completed a project that added exterior lighting to outdoor tennis courts, extending the hours they could be used by the public.

Justin Shaffer: Definitely. Providing access to fitness centers can be a great way to build goodwill within the community—particularly in rural areas where access to a YMCA or privately owned gym is limited.

Are there any safety concerns unique to the role the environment plays? For example, rural isolation versus urban density.

Glenn Niles: It’s not limited to rural districts, but one of the major shifts we’ve seen in the last few years that can create exterior safety concerns is the rise in parent drop-offs versus students taking the bus to get to and from school. A recent study showed that more than 50% of students are now dropped off by a parent or drive themselves to school in lieu of riding the school bus. Safety concerns arise when drop-off lanes, bus queues, and pedestrian paths converge. When designing school sites, we aim to ensure that parking lots, drive lanes, idling areas, and walking paths work together to keep students, staff, parents, and visitors safe—while alleviating as much traffic congestion as possible.

Courtney Ter Velde: When planning and assessing the best path forward, we’ve started utilizing drone photography and video to map traffic patterns during certain high-traffic times of day to identify challenges that arise during pickup and drop-off. This real-time data better informs the team and helps to design a site that is safe for all.

Have a specific question about rural design? Contact our experts—or come join us at the Rural Schools Association Conference, July 13-15 in Lake Placid, New York!

About the Author

Justin Shaffer, AIAArchitect/Project Manager

An Architect and Project Manager, Justin has 10 years of industry experience with a strong focus on K–12 educational facilities. He stays at the forefront of emerging trends and pedagogical shifts that drive modern school design. Justin’s project portfolio includes additions, renovations, and new construction, as well as building condition surveys and facility assessments.

About the Author

Courtney Ter-Velde, CID, ALEP, LEED GA, IIDASenior Interior Designer

As a NYS Certified Interior Designer, Courtney has over 10 years of experience in commercial interior design, with a focus in educational planning and K-12 design (Master Planning, CIP, COEP, and SED). Courtney’s expertise in educational and K-12 design includes programming, space planning, standardization, visualization, and the ability to customize and tailor each district’s needs through evidence-based design for social and emotional learning and student exploration. She is passionate about creating future forward learning environments that stimulate students and educators alike.

About the Author

Glenn Niles, Ed.D.K-12 Regional Manager

Glenn is a former superintendent and school administrator with over 25 years in education. As LaBella’s K-12 Regional Manager, he guides K-12 clients through strategic planning for capital projects, helping stakeholders navigate the Capital Improvement Program (CIP) process from an educational administrator’s perspective.