Developing Effective Hazard Plans in 2025

As new development advances across the country, our communities face increasingly complex challenges from both natural and man-made hazards. Municipalities are increasingly tasked with developing robust hazard plans to identify vulnerabilities amongst their communities, develop strategies and projects to address them, and pursue available funding opportunities to take hazard mitigation projects from concept to reality. In 2025, advancements in technology and climate modeling tools, along with a growing understanding of risk, will help design professionals and municipalities develop more effective strategies for hazard preparedness and mitigation. So what does a hazard mitigation plan look like, and what tools can we use in 2025 to enhance these plans moving forward?

The blueprint for these types of plans is relatively simple, but successful execution is often complex. Key steps include:

- Defining project goals and objectives and identifying stakeholders

- Identifying feasible hazards

- Assessing community and municipal vulnerabilities

- Adapting to changing conditions

- Recommending mitigation and adaptation measures

Defining Goals, Objectives, and Stakeholders

The first step for any successful project should be to clearly define goals, objectives, and key stakeholders. Examples of goals for a hazard mitigation plan are:

- Reduce the frequency and severity of flooding in a neighborhood in a given municipality.

- Identify the biggest hazards of concern for municipal operations.

- Identify how natural hazards are expected to change in a county over the next 50 years.

- Evaluate ways to adapt a community’s infrastructure to projected climate change to help target capital improvement investments.

Clearly defined goals allow the project team to seek out the appropriate data, tools, and project stakeholders required for a successful hazard mitigation plan. It is especially important to identify project stakeholders that will either be affected by the implementation of your goals or are integral to achieving these goals. Municipal leaders, residents, local businesses, nonprofit organizations, and religious institutions all play important roles during emergency situations and should be consulted during plan development.

Community input ensures that the plan addresses local realities and priorities, and consultants can then help refine objectives and provide technical expertise.

Identifying Hazards

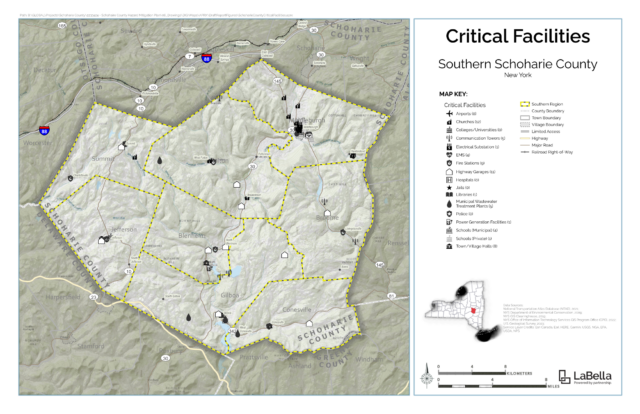

Identifying potential hazards is a foundational step in hazard planning. Hazards can be natural—such as floods, hurricanes, or wildfires—or man-made, including dam failures, gas line explosions, or industrial accidents. Determining the frequency, magnitude, and spatial threat of these hazards requires thorough analysis using historical data from trusted sources like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), as well as local records. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and other mapping tools also play a pivotal role in evaluating hazards. These tools provide insights into land cover, vulnerability zones, and spatial patterns, enabling planners to anticipate where individual hazards are likely to have the most significant impact.

The cascading effects of multiple hazards must also be understood. Natural hazards can be standalone events, or they can create a “domino effect”—for instance, a drought might trigger wildfires, or flooding may trigger a dam failure. GIS and other mapping tools are effective in helping to identify cascading hazards and the areas that could potentially be affected.

Assessing Vulnerabilities

Once hazards are identified, the next step is to assess vulnerabilities within the community. This involves evaluating populations, infrastructure, and natural habitats at risk from identified hazards. Engaging with local stakeholders through interviews and workshops provides valuable insights into vulnerabilities.

Additionally, reviewing hazard mapping tools like FEMA flood zone maps and Coastal Erosion Hazard Area (CEHA) data ensures a grounded and comprehensive analysis of risks. GIS and other mapping tools are important for identifying vulnerable populations and critical facilities, identifying important natural habitats, and creating an inventory of these vulnerable assets. One of the most common ways to quantify vulnerable assets is to compare their monetary value; however, it is recommended that public input and important natural areas be weighed heavily against a pure assessment of monetary value.

Adapting to Change

The hazard landscape is dynamic, influenced by climate change, technological advancements, and development patterns. Conducting climate hazard assessments using tools like the NOAA Climate Explorer helps communities predict how climate change will alter hazard frequency and intensity. Similarly, understanding new infrastructure developments or technological changes can inform how hazards are mitigated or amplified in specific areas.

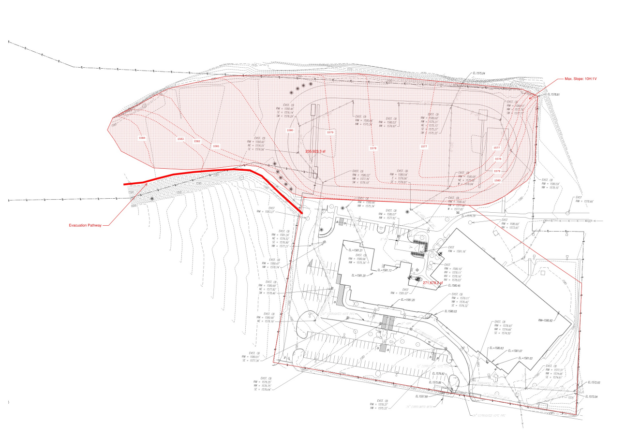

For example, development along tidally-influenced shorelines may require protective measures, such as structure elevation, dune nourishment, or even managed retreat. Other areas, such as inland developments near streams or rivers, may require flood mitigation solutions like floodplain expansion or structure elevation and floodproofing. Technological advances may also provide innovative solutions (e.g., early warning systems or resilient building materials) to mitigate risks.

Recommending Mitigation and Adaptation Measures

The culmination of hazard planning is the development of actionable mitigation and adaptation strategies. These measures can include:

- Capital Improvement Projects: Physical projects like expanding floodplains, upgrading heating and cooling systems, or relocating high-risk infrastructure.

- Institutional Controls and Legislation: Policy changes such as steep slope construction restrictions, floodplain ordinances, or expanded coastal hazard zones

- Climate-Adaptive Infrastructure: Forward-thinking designs that accommodate projected climate conditions, such as parks that double as flood storage areas or phased restrictions on developments in sea level rise zones.

Recommendations should be grounded in data and developed in collaboration with stakeholders. They should also identify potential funding sources, balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability.

Looking Forward

In 2025, hazard planning is not just about responding to today’s risks but anticipating tomorrow’s challenges. Hazard plans should seek to target public funding toward projects that enhance residents’ day-to-day lives while also protecting lives, property, and habitat during emergency events. Capital improvement projects, institutional controls and legislation, and climate-adaptive infrastructure should all be sized to accommodate the hazard events of both today and tomorrow. By leveraging advanced tools, fostering community collaboration, and prioritizing adaptive strategies, municipalities can create plans that protect their residents, improve their communities, and build resilience for decades to come.

About the Author

Jared Pristach, PE, WEDGSenior Environmental Engineer

Insights by Jared Pristach, PE, WEDG:

Jared brings his expertise in climate resilience and solar array development to his role as Senior Environmental Engineer, where he currently manages Brownfield Cleanup Program, shoreline resilience, and solar design projects. His experience includes Phase I and Phase II Environmental Site Assessments; New York State Department of Environmental Conservation State Superfund projects, with a focus on remedial design and construction oversight; remedial systems operation and maintenance; green infrastructure and civil engineering site design; shoreline and streambank resilience planning; and structural engineering design for recreational facilities.