Investing in Resilience: Designing Schools to Withstand Climate Change

Across the United States, schools are facing a new reality: buildings and ground once considered secure are now increasingly vulnerable to flooding, stormwater issues, and extreme heat. Rainfall events once thought of as “once in a century” now occur far more often, and aging drainage systems are struggling to keep up. Meanwhile, older classrooms grow uncomfortably hot as temperatures rise.

For districts focused first and foremost on teaching and learning, these challenges can feel daunting. But a range of cost-effective, nature-based solutions can help schools remain safe, comfortable, and resilient. By keeping schools open, reducing costly disruptions, and creating healthier environments for students and staff, these strategies directly support the core mission of education.

This article highlights three key environmental challenges, along with practical strategies for resilience.

Flooding: Planning Around the Water

A 2017 Pew Charitable Trusts study found that about 2.3% of U.S. public schools are located in flood zones—areas with at least a 1% annual chance of flooding. As rainfall becomes heavier and more frequent, even schools outside mapped floodplains face new risks.

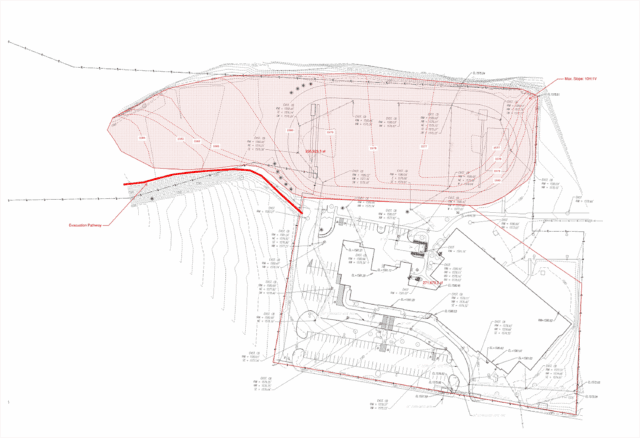

At Jasper-Troupsburg High School in Jasper, New York, flooding occurred in 2021 and 2024 despite the site being outside the mapped floodplain. The natural floodplain had been filled in during the 1990s to create athletic fields, reducing the site’s natural flood capacity. To prevent recurring flooding, the school district is working with LaBella to restore a portion of the natural floodplain, allowing the landscape to safely store water during storms and prevent flooding at the school building and in downstream neighborhoods.

To strengthen resilience against heavy rainfall, school districts should begin by assessing how and where flooding occurs, identifying areas at greatest risk. Open spaces—such as practice fields—can be intentionally designed to serve as temporary flood storage, directing water away from critical buildings and minimizing potential damage. When planning upgrades or new construction, districts should also call for engineering firms to incorporate future climate projections to ensure long-term resilience and protection.

Stormwater Management: Working With Nature

Stormwater systems in many schools were built decades ago and cannot handle today’s heavier storms. As these systems age, they naturally lose capacity without consistent upkeep, further exacerbating the potential for storm damage. Replacing them is often costly and disruptive—but there are smarter, more sustainable solutions.

At Minerva DeLand School in Fairport, New York, a small underground pipe carrying stormwater to the Erie Canal collapsed, damaging the athletic field. Instead of replacing the pipe, LaBella’s design team chose to “daylight” the small stream, restoring it to a natural channel. The result: greater stormwater capacity, reduced flood risk, improved habitat, and significant cost savings for the district.

While this specific solution may not be applicable to every school, districts can incorporate nature-based stormwater capture systems such as rain gardens, bioswales, permeable pavement, and naturalized channels to slow, capture, and infiltrate stormwater where it falls. Green infrastructure increases the capacity of existing stormwater systems, reduces maintenance needs, and can serve as an outdoor learning tool for students.

Capturing and infiltrating stormwater slows runoff to nearby creeks, rivers, and streams, reducing the intensity of flooding. Green infrastructure also promotes the use of native vegetation, enhancing aesthetics and improving the natural habitat.

Extreme Heat: Keeping Classrooms Comfortable

Although a quieter concern, heat is equally as troubling. Hot classrooms make it difficult for students to concentrate and can endanger health during prolonged heatwaves.

In New York State, recent legislation establishes maximum temperature limits for K–12 classrooms. Schools must take immediate actions to relieve heat-related discomfort when indoor temperatures reach 82°F, and classrooms cannot be occupied if temperatures exceed 88°F. Many schools—particularly in older buildings—will face significant challenges in meeting these requirements, from outdated electrical systems and limited space for mechanical upgrades to rising utility expenses.

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, an estimated 36,000 schools currently need to update or replace their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. As heatwaves become more frequent, the cost of installing and operating cooling systems will continue to rise.

Modest design and landscaping upgrades can have a significant impact. Planting shade trees, utilizing cool roofing materials or green roofs, installing energy-efficient windows, and maximizing natural ventilation all help lower temperatures inside and out while reducing energy consumption. Outdoor canopies or shaded courtyards can also make recess and outdoor learning safer and more enjoyable. Green infrastructure provides cooling benefits as well, helping to reduce urban heat island effects in addition to managing stormwater. These approaches not only improve comfort but also help schools meet regulatory requirements while supporting student well-being and performance.

School districts should actively look for opportunities to incorporate shade, energy efficiency, and ventilation improvements during routine upgrades or building projects to reduce long-term costs and enhance comfort year-round. By planning strategically—phasing in improvements, upgrading systems where feasible, and leveraging sustainable design—districts can maintain safe, functional, and productive learning environments even as temperatures continue to rise.

Building for the Future

Climate change is already reshaping the environments where students learn, and schools must evolve accordingly. By planning for flood risk, managing stormwater naturally, and mitigating extreme heat, districts can safeguard students, protect their facilities, and make smart investments in long-term resilience. Forward-thinking design not only strengthens infrastructure—it also creates safer, healthier, and more sustainable places to learn.

About the Author

Jared Pristach, PE, WEDGSenior Environmental Engineer

Jared brings his expertise in climate resilience and solar array development to his role as Senior Environmental Engineer, where he currently manages Brownfield Cleanup Program, shoreline resilience, and solar design projects. His experience includes Phase I and Phase II Environmental Site Assessments; New York State Department of Environmental Conservation State Superfund projects, with a focus on remedial design and construction oversight; remedial systems operation and maintenance; green infrastructure and civil engineering site design; shoreline and streambank resilience planning; and structural engineering design for recreational facilities.